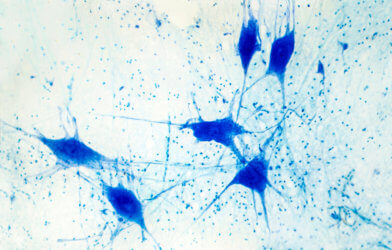

Most people are aware of music’s soothing abilities. According to Johns Hopkins Medicine, music has the potential to lower blood pressure and anxiety, as well as, enhance mood, sleep, and even memory. New research from the University of Colorado School of Medicine suggests that music also has the potential to treat Parkinson’s disease by re-wiring certain signal pathways of the brain.

Assistant Professor, Isabelle Buard, Ph.D., teaches Neurology at CU School of Medicine. She and her colleagues set out to investigate the effects of neurologic music therapy on individuals with Parkinson’s disease. This particular type of therapy involves rhythmic patterns and motor activities designed to alter the brain’s normal signal frequency.

“In Parkinson’s, beta frequencies are the most likely to be impaired,” said Buard. “The idea of the study is to use external rhythms that specifically target those frequencies by entraining them to a different level, modulating them to restore some kind of homeostasis in brain activity.”

Those with Parkinson’s meet with music therapists three days a week throughout the span of Buard’s research, which is supported by the National Institutes of Health. Each therapy exercise begins with coordination practice and repetitive hand/finger motions, followed by physical training with castanets (a type of drum) and keyboards with heavier keys for cognitive-motor therapy. Patients are instructed to do the activities at their leisure throughout the rest of the week. Tempos become faster and faster with each passing week of therapy.

To conduct her research, Buard divided the participants into four categories based on the type of therapy received. The first group received no form of therapy, the second group received the usual therapy given to Parkinson’s patients, the third group received neurologic music therapy wherein the tempo, or beat, was determined by the patient’s motions, and, the fourth group received the same cognitive therapy, however, therapists used a metronome to maintain a consistent beat.

Since rhythmic patterns outside of the brain are known to stimulate the brain, Buard hypothesized that those in the fourth group who were exposed to the metronome’s steady beat would benefit the most. “The idea is that if you’re doing internally generated movements, you rely on motor neuronal loops that are impaired in Parkinson’s, so you have some problems doing movements, or they are slow and not coordinated. When your movement is driven by external rhythms, then the movement seems to be easier to perform,” said Buard.

She and her team were looking for refined motor skills to justify this theory. “I’m looking at the networks that are mobilized during internally versus externally driven movement and trying to disentangle which different aspect is meaningful in terms of mobilization of brain networks,” added Buard.

Additionally, there is an opportunity for patients to engage in freestyle piano playing as part of cognitive music-based therapy. Earlier studies have shown that musical improvising can enhance mood and the feeling of contentment. “It seems to increase the quality of life for some people,” said Buard. “A lot of people feel very uncomfortable improvising at the beginning, but by the end, they’re very much liking it.”

According to Buard, she and the team aim to gather evidence over the course of the trial, testing motor coordination with a “grooved pegboard test,” which includes the correct movement of about 25 different pegs in order to be properly inserted into the board. Additionally, they will assess the overall standard of living along with feelings of stress and despair.

For individuals with Parkinson’s disease and other neurological conditions, the results could contribute to additional studies regarding therapy and rehabilitation measures. Furthermore, this study helps neurologists better understand the brain mechanisms exploited by music.

Buard believes that the research will ultimately bring about a musical therapeutic approach intervention that will enhance fine motor abilities in people with Parkinson’s.

“Right now, if you have fine motor difficulties due to Parkinson’s, your medications are not helping with that,” said Buard. “The medications help with gait and balance, and some medications help with tremors. But fine motor skills are not really handled well by medication therapy. It’s really a symptomatic approach, so if we find that it’s effective for Parkinson’s, we will do a larger clinical trial so that music therapy can be further approved as one of the clinical therapies for fine motor skills.”

This research is published in Trials.

Comments