Early brain development in the first month of embryonic life may impact whether schizophrenia occurs in adulthood, according to scientists with Weill Cornell Medicine. For years, scientists have hypothesized schizophrenia began in early development, but lacked proper evidence. Post-mortem studies of people with the disease found enlarged ventricles and anomalies in the cortical layers of the brain that likely were present in early life.

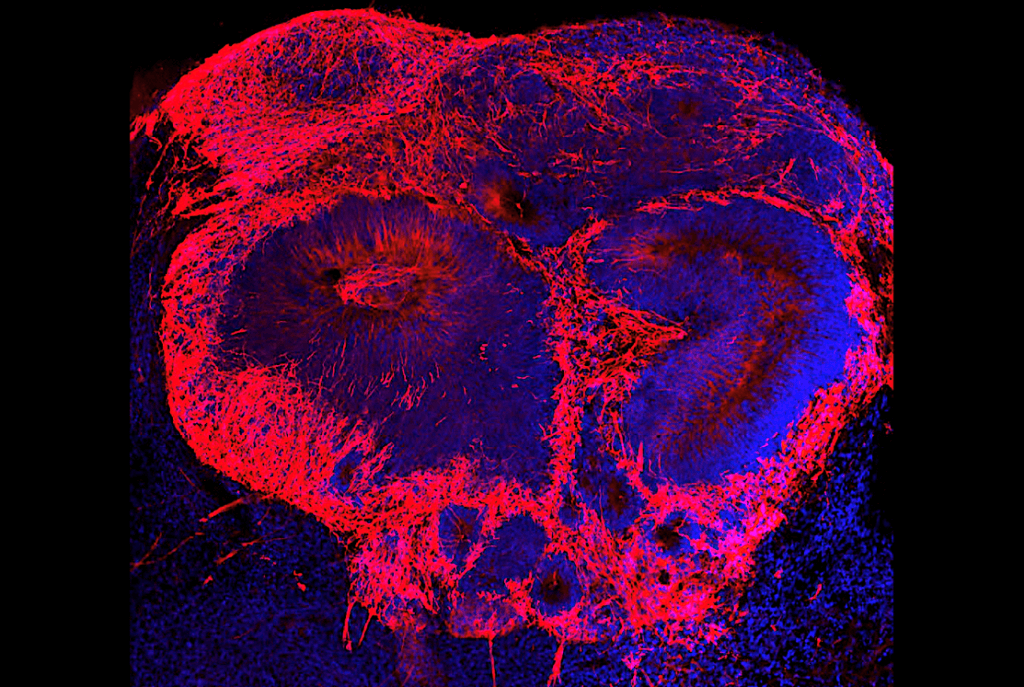

A recent study published in Molecular Psychiatry provided further insight into the link between early brain development and schizophrenia. In the study, researchers collected stem cells from 21 human stem cell donors to create three-dimensional “mini brains,” or organoids, in a laboratory environment. The donors were made up of those who had schizophrenia and others who did not have the disease. When comparing the organoids, researchers found a reduced expression of two specific genes needed for healthy brain development.

Among the researchers was senior author, Dilek Colak, assistant professor of neuroscience at the Feil Family Brain and Mind Institute and the Center for Neurogenetics at Weill Cornell Medicine. She and fellow author, Dr. Michael Notaras, team lead and a former NHMRC CJ Martin Fellow in Dr. Colak’s lab, collaborated on this study.

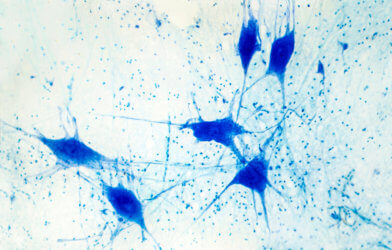

Notaras and his team were able to grow brain tissue with patients’ stem cells, using their exact genetic make-up. They then were able to take a close look at single cell RNA sequencing to determine gene expression in individual cells in the patient’s tissue. This was done for patients with and without schizophrenia.

The findings identified commonalities among the pathology samples of all patients with schizophrenia, despite the distinct way the disease presented among each patient. The samples had reduced expressions in two specific genes, BRN2 and pleiotrophin. BRN2 is a regulator of gene expression, and pleiotrophin is a cell growth promoter. Both of these genes are essential for brain development. The reduced expression of these genes resulted in reduced brain cell production and increased brain cell death. Researchers explored ways to replace the missing BRN2 in the cells, resulting in restored brain cell production, and also added pleiotrophin which minimized brain cell death.

“We’ve made a fundamental discovery providing what we think is the first evidence in human tissue that multiple cell-specific mechanisms exist and likely contribute to risk of schizophrenia,” Dr. Notaras says in a statement. “This forces us, as a field, to reconsider when disease truly begins and how we should think about developing the next generation of schizophrenia therapeutics.”

The results of this study provide a path forward for more research to be conducted on schizophrenia and other brain diseases. Specialized therapies could be targeted and produced to help correct these genetic brain cell abnormalities.

Dr. Colak is hopeful the creation of “mini brains” grown from patients’ stem cells may have benefits far beyond this particular study on schizophrenia. “The technique could be used to study the early life pathology of late-onset neuropsychiatric or neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s disease or Huntington disease,” she says.

This study is published in the journal Molecular Psychiatry

Article by Elizabeth Bartell

Comments