There are many different types of dementia, such as Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia (FTD), all with different symptoms, affecting different parts of the brain. In a new study, scientists at the University of Cambridge identify the mechanism responsible for the one symptom common to all types of dementia.

The finding offers hope that focusing new treatments on this common defect could enhance management of all types of dementia.

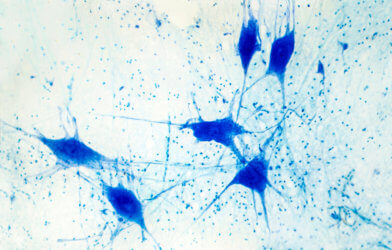

Dementias are characterized by the build-up of different toxic proteins in different parts of the brain. The symptoms are varied, such as problems with memory, speech, behavior, or vision. The one symptom common to all types of dementia is difficulty in responding to change, especially unexpected situations. The difficulty is due to damage to areas of the brain called multiple demand networks. These areas are highly evolved, supporting general intelligence.

“At the heart of all dementias is one core symptom, which is that when things change or go unexpectedly, people find it very difficult,” explains Dr. Thomas Cope, from the MRC Cognition and Brain Science Unit and Department of Clinical Neurosciences at Cambridge, in a statement. “If people are in their own environment and everything is going to plan, then they are OK. But as soon as the kettle’s broken or they go somewhere new, they can find it very hard to deal with.”

Cope and colleagues analyzed data from 75 patients, each with one of four types of dementia, each type affecting a different area of the brain. The control group consisted of 48 individuals without dementia.

The participants’ brain activity was recorded by a magnetoencephalography device. It measures the tiny magnetic fields produced by the electrical currents associated with activity in the brain. These machines allow very precise timing of brain activity.

During the scan, the volunteers watched a film in which the soundtrack was replaced by a series of beeps. The beeps had a consistent pattern, with different beeps superimposed at random. These additional beeps were different, such as higher-pitched, or at a different volume.

Each intercalated beep triggered two responses in the brain. The first response was immediate, followed by a second response about a fifth of a second after the first. The immediate response was generated in the auditory system, triggered by recognition that a beep had occurred. These responses were the same in all the participants.

The following response indicated that the beep was unusual. This response was lesser among the people with dementia than among the healthy participants, indicating that the brains with dementia were less effective at recognizing that something had changed.

The researchers looked at which brain areas were activated during the task and combined their data with that from MRI scans, which showed the structure of the brain. They showed that damage to areas of the brain known as ‘multiple demand networks’ was associated with a reduction in the later response.

Multiple demand networks, are involved in general intelligence – for example, in problem-solving. It is these networks that allow us to be flexible in our environment. In healthy volunteers, the sound is picked up by the auditory system, which relays information to the multiple demand network to be processed and interpreted.

“There’s a lot of controversy about what exactly multiple demand networks do and how involved they are in our basic perception of the world,” says Dr. Cope. “There’s been an assumption that these intelligence networks work ‘above’ everything else, doing their own thing and just taking in information. But what we’ve shown is no, they’re fundamental to how we perceive the world.

“That’s why we can look at a picture and immediately pick out the faces and the relevant information,” he continues, “whereas somebody with dementia will look at that scene a bit more randomly and won’t immediately pick out what’s important.”

The research reinforces advice given to dementia patients and their families, notes Dr Cope. “The advice I give in my clinics is that you can help people who are affected by dementia by taking a lot more time to signpost changes, flagging to them that you’re going to start talking about something different or you’re going to do something different. And then repeat yourself more when there’s a change, and understand why it’s important to be patient as the brain recognizes the new situation.”

The research is published in The Journal of Neuroscience.