Let food be thy medicine and medicine be thy food. -Hippocrates

Studies of appetite, eating disorders, overweight, and obesity, have focused on a part of the brain called the hypothalamus. It’s a cone-shaped structure that projects downward from the brain. Although it’s small, it’s busy – important to regulation of many hormones, emotional responses, body temperature, sexual behavior, and appetite control.

Newer research looks beyond the hypothalamus, at several brain pathways that meet in the primitive brain stem. These pathways are important to the control of feeding behaviors, including satiety – the signal to stop eating.

“Everything the hypothalamus does ends up converging in the brainstem,” says Dr. Martin, a professor of internal medicine at the University of Michigan, and director of the school’s Elizabeth Weiser Caswell Diabetes Institute, in a statement. “The brain stem is super important in the control of feeding because it takes all sorts of information from your gut, including whether the stomach is distended and whether nutrients have been ingested, and integrates this with information from the hypothalamus about nutritional needs before passing it all on to the rhythmic pattern generators that control food intake.”

Dr. Tune Pers, from the University of Copenhagen, and his group collaborated with Myers. They used single-cell mapping of neurons within the dorsal vagal complex, a region in the brain stem associated with unconscious processes, including a sense of satiety after eating.

Researchers integrated their collective findings with other recent discoveries to create a new model of brain stem circuits which control food intake and nausea. “Taking all of this information together allows us to predict which set of neurons controls this or that function,” says Myers.

The scientists’ work with various cell populations has revealed many targets for new obesity-fighting drugs, such as a class of drugs, GLP1 receptor agonists, that lower blood sugar and decrease food intake.

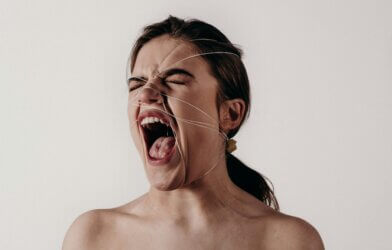

“There is a population of GLP1 neurons in the brain stem which, if you turn them on, will stop food intake but cause violent illness, but there may be another population of neurons that stops eating without making you feel badly,” Myers said.

Having a detailed map of these neurons and understanding the effects of modifying these cell targets, Myers explains, can assist in creating drugs with fewer negative side effects.

The study is published in the journal Nature Metabolism.

-392x250.jpg)