Alzheimer’s disease could be detected years before symptoms begin thanks to a simple smell test, according to new research. Losing the olfactory sense, known as anosmia, is one of the first symptoms of the disease, say scientists.

The test predicts changes in brain regions important in dementia – opening the door to a cheap and non-invasive screening program. They would be as routine as going to the doctor to check out your vision or hearing. Clinical trials are now being planned.

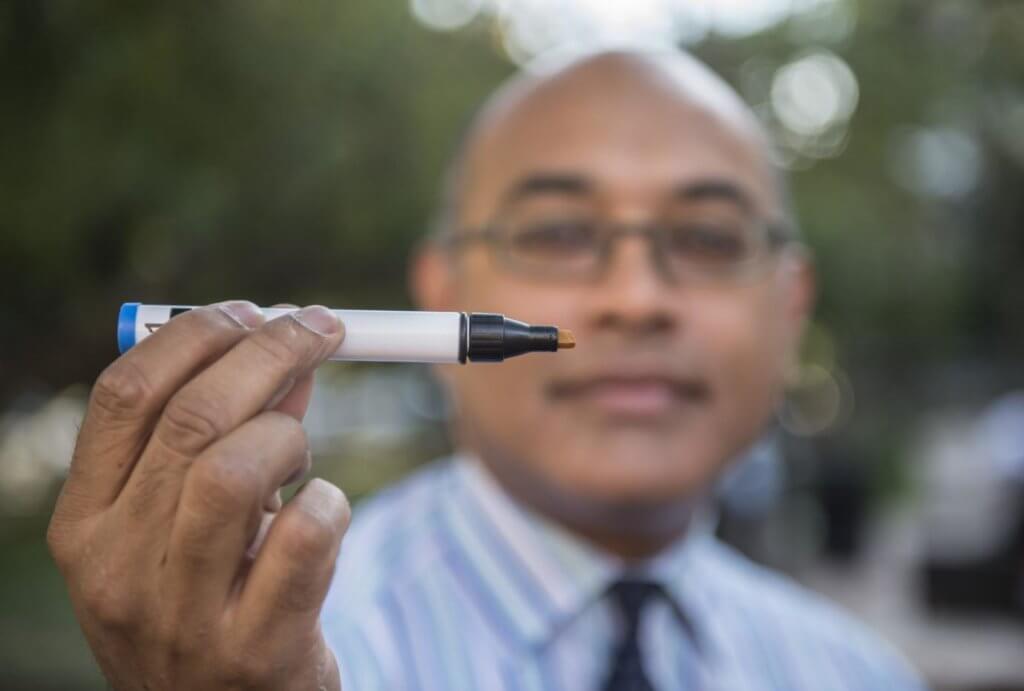

“This study provides another clue to how a rapid decline in the sense of smell is a really good indicator of what’s going to end up structurally occurring in specific regions of the brain,” says senior author, Jayant Pinto, a professor of surgery at the University of Chicago, in a statement.

Early diagnosis is vital. Drugs trials have failed so far because they are prescribed too late, once the memory-robbing condition has taken hold. Memory plays a critical role in our ability to recognize odors. Scientists have long known of a link between sense of smell and dementia.

Alzheimer’s disease is believed to be triggered by plaques and tangles of rogue proteins that gather in neurons that control olfaction and memory, then spread to others.

Putting smell to the test for Alzheimer’s

Smell tests are an inexpensive and easy-to-use. The tool described in Alzheimer’s & Dementia consists of a series of sticks that are similar in appearance to felt-tip pens. Each is infused with a distinct scent that individuals must identify from a set of four choices.

The team analyzed data on 515 older Americans who had been taking part in a memory and aging project since 1997. They demonstrated it was possible to identify alterations in the brain that correlated with an individual’s loss of smell and cognitive function over time.

“Our idea was people with a rapidly declining sense of smell over time would be in worse shape – and more likely to have brain problems and even Alzheimer’s itself – than people who were slowly declining or maintaining a normal sense of smell,” says lead author Rachel Pacyna, a rising star in her fourth-year as a medical student.

Participants are tested annually for cognitive function, signs of dementia and their ability to identify certain smells. Some have also received an MRI brain scan. A rapid decline in olfactory skills during a period of normal cognition predicted multiple features of Alzheimer’s disease. They included less grey matter in areas related to smell and memory, worse cognition and higher risk of dementia.

In fact, the risk of sense of smell loss was similar to carrying the APOE-e4 mutation, a known genetic risk factor for Alzheimer’s.

The changes were most noticeable in primary olfactory regions called the amygdala and entorhinal cortex. They are linked to the hippocampus, which is the memory control center and a critical site in Alzheimer’s.

“We were able to show the volume and shape of gray matter in olfactory and memory-associated areas of the brains of people with rapid decline in their sense of smell were smaller compared to people who had less severe olfactory decline,” says Pinto.

Early detection key in treatment and prevention

An autopsy is the gold standard for confirming Alzheimer’s disease. Pinto hopes to eventually extend the findings by examining patient brain tissue. Smell tests in clinics are also being planned – in ways similar to how vision and hearing tests are used. Older adults would be screened and tracked for early-doors dementia. It could lead to the development of new treatments.

Bigger studies taking more MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) brain scans may help pinpoint when structural changes in the brains begin – or how quickly they shrink.

“We have to take our study in the context of all of the risk factors that we know about Alzheimer’s, including the effects of diet and exercise,” adds Pinto. “Sense of smell and change in the sense of smell should be one important component in the context of an array of factors that we believe affect the brain in health and aging.”

He has previously examined sense of smell as an important marker for declining health in older adults. It’s often overlooked, compared to our ability to see and hear.

The number of dementia cases worldwide will triple to over 150 million by 2050. New treatments are desperately needed, and early diagnosis is key.

Report by Mark Waghorn, South West News Service